Thankfully in 2015 most (but not all) proprietary software providers have moved away from the archaic ideology of software being licensed by the CPU core – a concept that reflected the value and importance of systems back when you were buying physical hardware, but rendered completely meaningless by cloud and virtualisation providers.

Taking it’s place came the subscription model, popularised by Software-as-a-Service (or “cloud”) products. The benefits are attractive – regular income via customer renewal payments, flexibility for customers wanting to change the level of product or number of systems covered and no CAPEX headaches in acquiring new products to use.

Clients win, vendors win, everyone is happy!

Or maybe not.

Whilst the horrible price-by-CPU model has died off, a new model has emerged – price by server. This model assumes that the more servers a customer has, the bigger they are and the more we should charge them.

The model makes some sense in a traditional virtualised environment (think VMWare) where boxes are sliced up and a client runs only as many as they need. You might only have a total of two servers for your enterprise application – primary and DR – each spec’ed appropriately to handle the max volume of user requests.

But the model fails horribly when clients start proper cloud adoption. Suddenly that one big server gets sliced up into 10 small servers which come and go by the hour as they’re needed to supply demand.

DevOps techniques such as configuration management suddenly turns the effort of running dozens of servers into the same as running a single machine, there’s no longer any reason to want to constrain yourself to a single machine.

It gets worse if the client decides to adopt microservices, where each application gets split off into it’s own server (or container aka Docker/CoreOS). And it’s going to get very weird when we start using compute-less computing more with services like Lambda and Hoist because who knows how many server licenses you need to run an application that doesn’t even run on a server that you control?

Really the per-server model for pricing is as bad as the per-core model, because it no longer has any reflection on the size of an organisation, the amount they’re using a product and most important, the value they’ve obtaining from the product.

So what’s the alternative? SaaS products tend to charge per-user, but the model doesn’t always work well for infrastructure tools. You could be running monitoring for a large company with 1,000 servers but only have 3 user accounts for a small sysadmin team, which doesn’t really work for the vendor.

Some products can charge based on volume or API calls, but even this is risky. A heavy micro-service architecture would result in large number of HTTP calls between applications, so you can hardly say an app with 10,000 req/min is getting 4x the value compared to a client with a 2,500 req/min application – it could be all internal API calls.

To give an example of how painful the current world of subscription licensing is with modern computing, let’s conduct a thought exercise and have a look at the current pricing model of some popular platforms.

Let’s go with creating a startup. I’m going to run a small SaaS app in my spare time, so I need a bit of compute, but also need business-level tools for monitoring and debugging so I can ensure quality as my startup grows and get notified if something breaks.

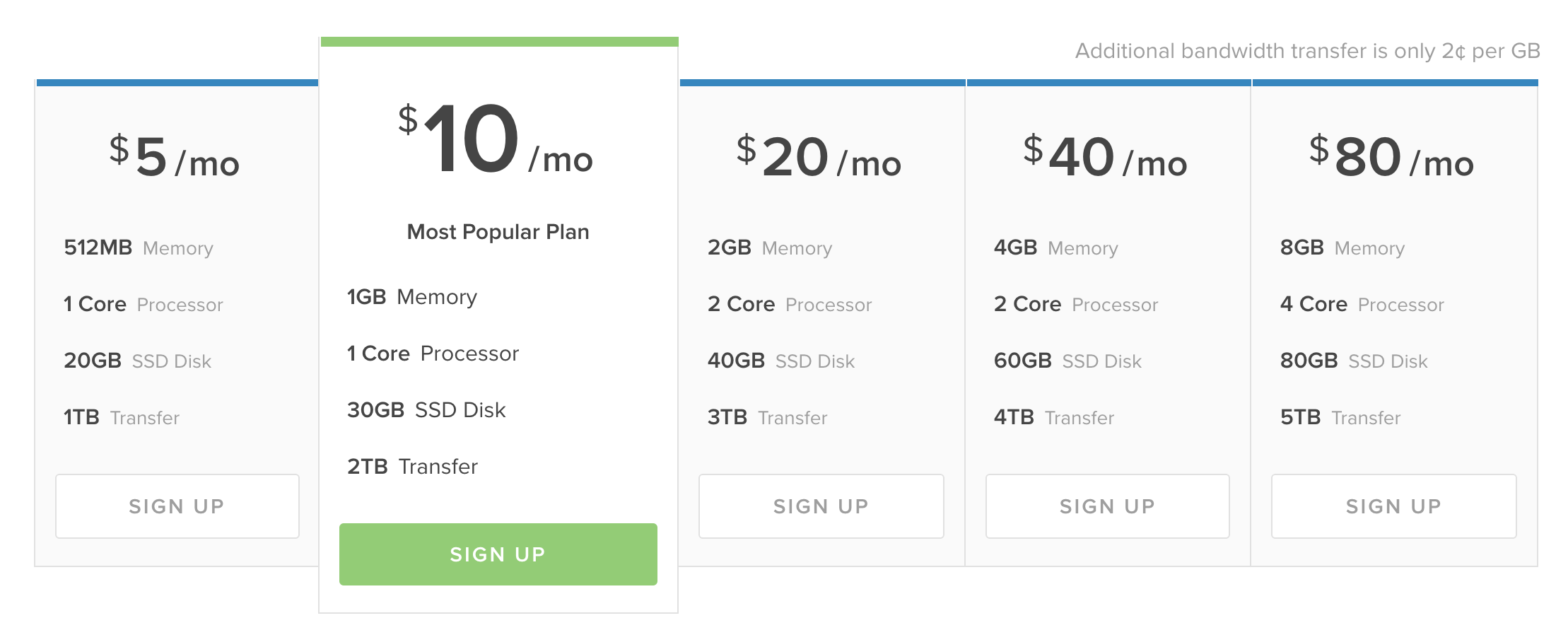

First up I need compute. Modern cloud compute providers *understand* subscription pricing. Their models are brilliantly engineered to offer a price point for everyone. Whether you want a random jump box for $2/month or a $2000/month massive high compute monster to crunch your big-data-peak-hipster-NoSQL dataset, they can deliver the product at the price point you want.

Let’s grab a basic Digital Ocean box. Well actually let’s grab 2, since we’re trying to make a redundant SaaS product. But we’re a cheap-as-chips startup, so let’s grab 2x $5/mo box.

Ok, so far we’ve spent $10/month for our two servers. And whilst Digital Ocean is pretty awesome our code is going to be pretty crap since we used a bunch of high/drunk (maybe both?) interns to write our PHP code. So we should get a real time application monitoring product, like Newrelic APM.

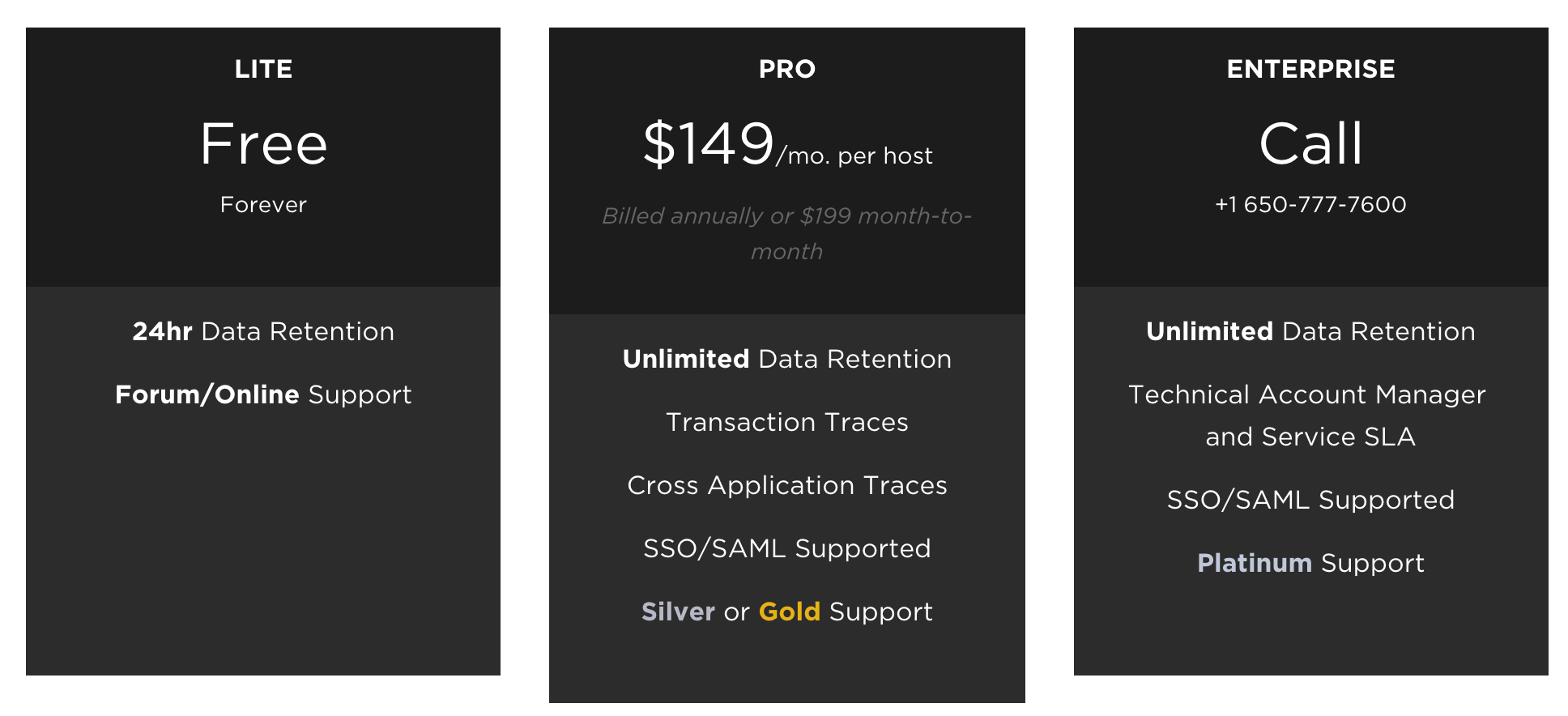

Woot! Newrelic have a free tier, that’s great news for our SaaS application – but actually it’s not really that useful, it can’t do much tracing and only keeps 24 hours history. Certainly not enough to debug anything more serious than my WordPress blog.

I’ll need the pro account to get anything useful, so let’s add a whopping $149/mo – but actually make that $298/mo since we have two servers. Great value really. :-/

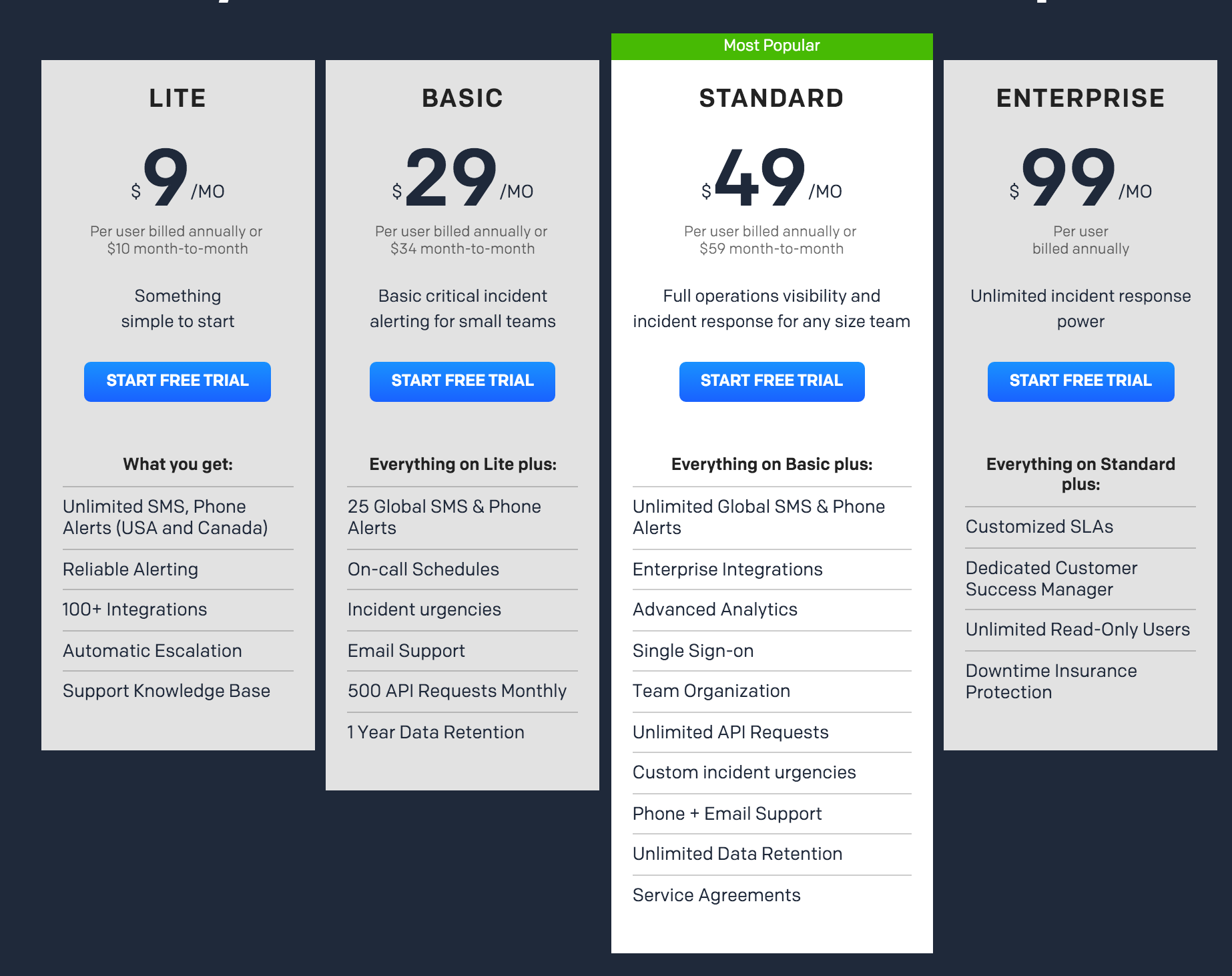

Next we probably need some kind of paging for oncall when our app blows up horribly at 4am like it will undoubtably do. PagerDuty is one of the popular market leaders currently with a good reputation, let’s roll with them.

Hmm I guess that $9/mo isn’t too bad, although it’s essentially what I’m paying ($10/mo) for the compute itself. Except that it’s kinda useless since it’s USA and their friendly neighbour only and excludes us down under. So let’s go with the $29/mo plan to get something that actually works. $29/mo is a bit much for a $10/mo compute box really, but hey, it looks great next to NewRelic’s pricing…

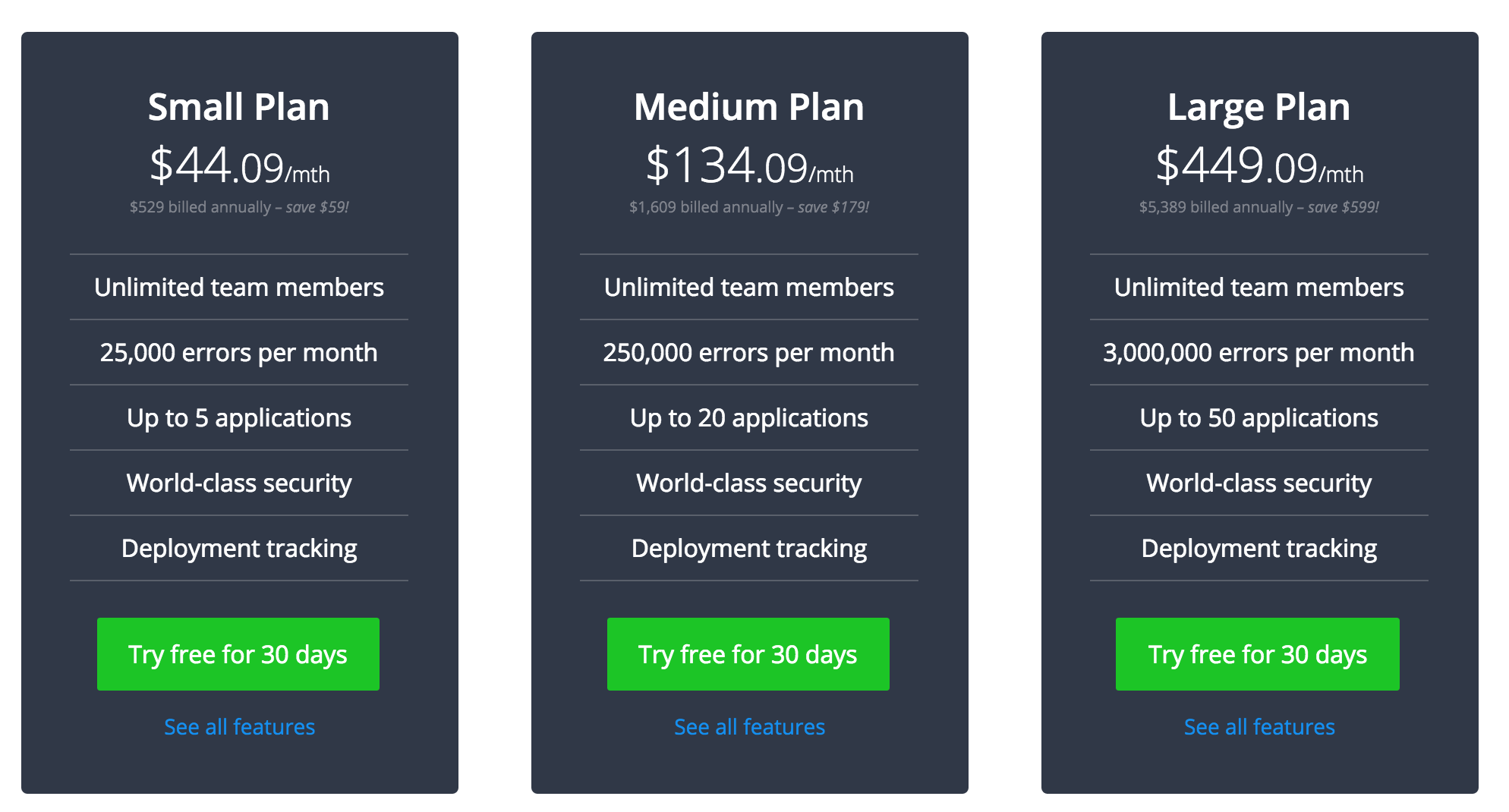

Remembering that my SaaS app is going to be buggier than Windows Vista, I should probably get some error handling setup. That $298/mo Newrelic APM doesn’t include any kind of good error handler, so we should also go get another market leader, Raygun, for our error reporting and tracking.

For a small company this isn’t bad value really given you get 5 different apps and any number of muppets working with you can get onboard. But it’s still looking ridiculous compared to my $10/mo compute cost.

So what’s the total damage:

Compute: $10/month

Monitoring: $371/month

Ouch! Now maybe as a startup, I’ll churn up that extra money as an investment into getting a good quality product, but it’s a far cry from the day when someone could launch a new product on a shoestring budget in their spare time from their uni laptop.

Let’s look at the same thing from the perspective of a large enterprise. I’ve got a mission critical business application and it requires a 20 core machine with 64GB of RAM. And of course I need two of them for when Java inevitably runs out of heap because the business let muppets feed garbage from their IDE directly into the JVM and expected some kind of software to actually appear as a result.

That compute is going to cost me $640/mo per machine – so $1280/mo total. And all the other bits, Newrelic, Raygun, PagerDuty? Still that same $371/mo!

Compute: $1280/month

Monitoring: $371/month

It’s not hard to imagine that the large enterprise is getting much more value out of those services than the small startup and can clearly afford to pay for that in relation to the compute they’re consuming. But the pricing model doesn’t make that distinction.

So given that we know know that per-core pricing is terrible and per-server pricing is terrible and (at least for infrastructure tools) per-user pricing is terrible what’s the solution?

“Cloud Spend Licensing” [1]

[1] A term I’ve just made up, but sounds like something Gartner spits out.

With Cloud Spend Licensing, the amount charged reflects the amount you spend on compute – this is a much more accurate indicator of the size of an organisation and value being derived from a product than cores or servers or users.

But how does a vendor know what this spend is? This problem will be solving itself thanks to compute consumers starting to cluster around a few major public cloud players, the top three being Amazon (AWS), Microsoft (Azure) and Google (Compute Engine).

It would not be technically complicated to implement support for these major providers (and maybe a smattering of smaller ones like Heroku, Digital Ocean and Linode) to use their APIs to suck down service consumption/usage data and figure out a client’s compute spend in the past month.

For customers whom can’t (still on VMWare?) or don’t want to provide this data, there can always be the fallback to a more traditional pricing model, whether it be cores, servers or some other negotiation (“enterprise deal”).

How would this look?

In our above example, for our enterprise compute bill ($1280/mo) the equivalent amount spent on the monitoring products was 23% for Newrelic, 3% for Raygun and 2.2% for PagerDuty (total of 28.2%). Let’s make the assumption this pricing is reasonable for the value of the products gained for the sake of demonstration (glares at Newrelic).

When applied to our $10/month SaaS startup, the bill for this products would be an additional $2.82/month. This may seem so cheap there will be incentive to set a minimum price, but it’s vital to avoid doing so:

- $2.82/mo means anyone starting up a new service uses your product. Because why not, it’s pocket change. That uni student working on the next big thing will use you. The receptionist writing her next mobile app success in her spare time will use you. An engineer in a massive enterprise will use you to quickly POC a future product on their personal credit card.

- $2.82/mo might only just cover the cost of the service, but you’re not making any profit if they couldn’t afford to use it in the first place. The next best thing to profit is market share – provided that market share has a conversion path to profit in future (something some startups seem to forget, eh Twitter?).

- $2.82/mo means IT pros use your product on their home servers for fun and then take their learning back to the enterprise. Every one of the providers above should have a ~ $10/year offering for IT pros to use and get hooked on their product, but they don’t. Newrelic is the closest with their free tier. No prizes if you guess which product I use on my personal servers. Definitely no prizes if you guess which product I can sell the benefits of the most to management at work.

But what about real earnings?

As our startup grows and gets bigger, it doesn’t matter if we add more servers, or upsize the existing ones to add bigger servers – the amount we pay for the related support applications is always proportionate.

It also caters for the emerging trend of running systems for limited hours or using spot prices – clients and vendor don’t have to worry about figuring out how it fits into the pricing model, instead the scale of your compute consumption sets the price of the servers.

Suddenly that $2.82/mo becomes $56.40/mo when the startup starts getting successful and starts running a few computers with actual specs. One day it becomes $371 when they’re running $1280/mo of compute tier like the big enterprise. And it goes up from there.

I’m not a business analyst and “Cloud Spend Licensing” may not be the best solution, but goddamn there has to be a more sensible approach than believing someone will spend $371/mo for their $10/mo compute setup. And I’d like to get to that future sooner rather than later please, because there’s a lot of cool stuff out there that I’d like to experiment with more in my own time – and that’s good for both myself and vendors.

Other thoughts:

- “I don’t want vendors to see all my compute spend details” – This would be easily solved by cloud provider exposing the right kind of APIs for this purpose eg, “grant vendor XYZ ability to see sum compute cost per month, but no details on what it is“.

- “I’ll split my compute into lots of accounts and only pay for services where I need it to keep my costs low” – Nothing different to the current situation where users selectively install agents on specific systems.

- “This one client with an ultra efficient, high profit, low compute app will take advantage of us.” – Nothing different to the per-server/per-core model then other than the min spend. Your client probably deserves the cheaper price as a reward for not writing the usual terrible inefficient code people churn out.

- “This doesn’t work for my app” – This model is very specific to applications that support infrastructure, I don’t expect to see it suddenly being used for end user products/services.